- May 14, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 3, 2023

We’re all unique snowflakes, each of us offering a one-of-a-kind perspective of our time here on Earth. That much is for sure. Yet for some minority groups, their unique experience of the world requires adjustments to be made, so that they can navigate the architecture, technology, and tools created, almost entirely, by the majority group.

For many disabled designers, this imbalance has to change. Calling for inclusivity and accessibility in design, they confront topics of disability and bias in their works. Designers Shannon Finnegan and Ryan Seslow all agree that their disabilities have honed their creativity, and allowed them to develop a specialized set of skills. We spoke to them about design, inclusivity, and getting themselves heard:

We spoke to them about design, inclusivity, and getting themselves heard:

Shannon Finnegan: Representing disabilities with candor and nuance

According to Brooklyn-based designer and artist Shannon Finnegan, many designers get accessibility wrong. “Accessibility is not in conflict with good design,” she proclaims. “For me, a design that centers accessibility is the best, most beautiful design.”

She calls for accessible design to be more than a mere checklist meant to walk you through the motions of some to-dos. Instead, accessibility can be an act of inclusion stemming from a deeper and more authentic understanding of the needs and wants of disabled communities.

They are communities, Shannon says, that she’s proud to represent in her design work and have as an audience. “We are funny, vibrant, and nuanced. Mainstream culture never treats us that way or shows us a real vision of ourselves. We have to do that for each other.”

Her Anti-Stairs Club Lounge project is a good example of her humorous and feisty treatment of accessibility topics. The project, located on the ground floor of the Wassaic Project’s exhibition space in New York, addresses the inaccessibility of the space. The upper floors of the historical, seven-floor building is inaccessible for people with mobility impairments.

As a form of protest, Shannon created a colorful, welcoming lounge for those waiting on the first floor until their families and friends returned from their tour upstairs. “I wanted to make their experience of the exhibition richer and more fun, adding to their stay on the ground floor,” she tells us.

The resulting installation is a fully-branded lounge offering cozy seating, refreshments, a logo of a crossed-out staircase, and a mural that says, “The higher you climb, the farther you fall” in stair-inspired typography. The project has since expanded to include an iteration at the New York Vessel landmark, a beehive-shaped building of 154 flights of steps.

While promoting design work on Instagram, Shannon makes a point of adding image descriptions for each of the posts on her feed. “It’s important for me to be proactive about making my work accessible, and build it [accessibility] into my creative process,” she explains.

While she was nervous at first about describing her design work in writing, the habit grew on Shannon and she now enjoys coming up with image descriptions for her work. “I really enjoy thinking about the image, thinking about what I’m trying to express with it, and then writing something that I feel matches that tone,” she reflects. It’s a small example of how a practice that originates out of a sense of responsibility, can with time grow into a meaningful creative habit.

Ryan Seslow: Visual comments on human communication

Ryan Seslow is a New York-based graphic designer and a professor of art and design. He’s deaf and hard of hearing, which to him, means “my eyes are also my ears.” Ryan explains that going about life, he’s “in a perpetual state of straining and overcompensating. I overcompensate visually for what I’m missing.”

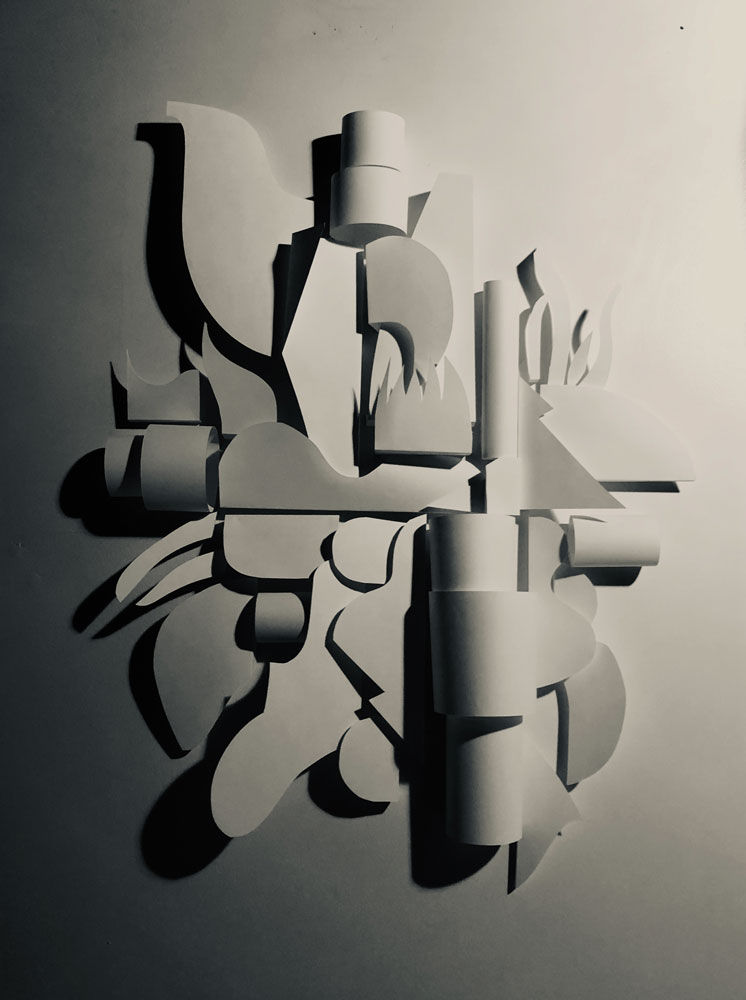

This constant search for more visual cues finds its way into his design work. “I like the tension between order and chaos, minimalism and overstimulation,” he says. “I’m clearly addicted to that as an energy.”

The visual work he creates is saturated with color and movement, his compositions often jam-packed with many elements. Most of his works deal with modes of communication or communication technology, expressing his interest in how “we, as human beings, are mediums of communication.”

“Being deaf and hard of hearing has given me the opportunity to form my own unique understanding of the world that I participate in,” Ryan remarks. As an example, he goes back to his elementary school days, saying he missed all of it. “My body was there, but I couldn’t hear my teachers so I had to develop an alternative understanding of what I thought I was missing.”

But thanks to current-day technology, Ryan says that these kinds of excluding experiences can be easily avoided. “Technology is wonderful. I believe that it will only get better and better,” he comments. In professional interactions, such as working with clients, he usually uses email, text messages, or video chats, where he can see the person speaking.

Yet because of the relative ease of achieving full accessibility today, Ryan’s even more disappointed when it’s mistakenly overlooked as a minor detail. Videos without captions or sufficient visual information bother him. “It’s so easy to do today,” he points out.

To live up to the mission of greater inclusivity, Ryan stresses the importance of including people with disabilities on work teams. “Reach out to people with disabilities and hire them,” he suggests. “With influence, comes greater responsibility.”

Want to learn more about designing with disabilities in mind? The DIS Wix website will put you on the right path with an expertly-curated reading list.